maybe the textgen content apocalypse is great

maybe the textgen content apocalypse is great

- quick read

- Posted in rp

maybe the textgen content apocalypse is great

maybe the textgen content apocalypse is great

CDL: The AAP is Wrong About Everything

CDL: The AAP is Wrong About Everything

In going through these arguments, I’ll also be drawing from a few other sources, in order to give a more comprehensive description of the arguments being made.

The Authors Guild Amici Curiae Brief is a document submitted to the court by The Authors Guild in support of the plaintiff’s argument.

Reflections from the Association of American Publishers on Hachette Book Group v. Internet Archive: An Affirmation of Publishing is a victory-lap publication from the AAP, published after the summary judgement in favor of the plaintiffs.

And there’s also EFF, Redacted Memorandum of Law In Support of Defendant Internet Archive’s Motion for Summary Judgment, written by the EFF in support of the Internet Archive, and whose arguments overlap a lot with mine.

Alright, there’s never anything more damning than their own words, so let’s just look at what it is they said here.

CDL: Publishers Against Books

CDL: Publishers Against Books

Combining lending with digital technology is tricky to do within the constraints of copyright. But it’s important to still be able to lend, especially for libraries. With a system called Controlled Digital Lending, libraries like the Internet Archive (IA) made digital booklending work within the constraints of copyright, but publishers still want to shut it down. It’s a particularly ghoulish example of companies rejecting copyright and instead pursuing their endless appetite for profit at the expense of everything worthwhile about the industry.

Notes on the VRC Creator Economy

Notes on the VRC Creator Economy

My friend Floober brought some recent changes VRChat is making in chat, and I thought I’d jot down my thoughts.

The problem with the VRC economy is the same problem as with most “platform economies”: everyone is buying lots in a company town.

This was the precipitating announcement: VRChat releasing a beta for an in-game real-money store.

Paid Subscriptions: Now in Open Beta! — VRChat Over the last few years, we’ve talked about introducing something we’ve called the “Creator Economy,” and we’re finally ready to reveal what the first step of that effort is going to look like: Paid Subscriptions!

As it stands now, creators within VRChat have to jump through a series of complicated, frustrating hoops if they want to make money from their creations. For creators, this means having to set up a veritable Rube Goldberg machine, often requiring multiple external platforms and a lot of jank. For supporters, it means having to sign up for those same platforms… and then hope that the creator you’re trying to support set everything up correctly.

(The problem, of course, is that “frustrating jank” was designed by VRChat, and their “solution” is rentiering.)

Currently, the only thing to purchase is nebulous “subscriptions” that would map to different world or avatar features depending on the content. But more importantly, this creates a virtual in-game currency, and opens the door to future transaction opportunities. I’m especially thinking of something like an avatar store.

I quit playing VRChat two years ago, when they started to crack down on client-side modifications (which are good) by force-installing malware (which is bad) on players’ computers. Since then I’ve actually had a draft sitting somewhere about software architecture in general, and how you to evaluate whether it’s safe or a trap. And, how just by looking at the way VRChat is designed, you can tell it’s a trap they’re trying to spring on people.

Currently, the VRC Creator Economy is just a currency store and a developer api. Prior to this, there was no way for mapmakers to “charge users” for individual features; code is sandboxed, and you only know what VRC tells you, so you can’t just check against Patreon from within the game1.

But the real jackpot for VRC is an avatar store. Currently, the real VRC economy works by creators creating avatars, maps, and other assets in the (mostly-)interchangeable Unity format, and then selling those to people. Most commonly this is seen in selling avatars, avatar templates, or custom commissioned avatars. Users buy these assets peer-to-peer.

This is the crucial point: individuals cannot get any content in the game without going through VRC. When you play VRChat, all content is streamed from VRChat’s servers anonymously by the proprietary client. There are no URLs, no files, no addressable content of any kind. (In fact, in the edge cases where avatars are discretely stored in files, in the cache, users get angry because of theft!) VRChat isn’t a layer over an open protocol, it’s its own closed system. Even with platforms like Twitter, at least there are files somewhere. But VRChat attacks the entire concept of files, structurally. The user knows nothing and trusts the server, end of story.

How Nintendo Misuses Copyright

How Nintendo Misuses Copyright

When I’m looking for an example of copyright abuse, I find myself returning to Nintendo a lot on this blog. Nintendo is a combination hardware/software/media franchise company, so they fit a lot of niches. They’re a particularly useful when talking about IP because the “big N” is both very familiar to people and also egregiously bad offenders, especially given their “friendly” reputation.

Nintendo has constructed a reputation for itself as a “good” games company that still makes genuinely fun games with “heart”. Yet it’s also infamously aggressive in executing “takedowns”: asserting property ownership of creative works other people own and which Nintendo did not make.

You’d think a company like Nintendo — an art creation studio in the business of making and selling creative works — would be proponents of real, strong, immutable creative rights. That, as creators, they’d want the sturdiest copyright system possible, not one compromised (or that could be compromised) to serve the interests of any one particular party. This should be especially true for Nintendo even compared to other studios, given Nintendo’s own fight-for-its-life against Universal, its youth, and its relatively small position1 in the market compared to its entertainment competitors Disney, Sony, and Microsoft.

But no, Nintendo takes the opposite position. When it comes to copyright, they pretty much exclusively try to compromise it in the hopes that a broken, askew system will end up unfairly favoring them. And so they attack the principles of copyright, viciously, again and again, convinced that the more broken the system is, the more they stand to profit.

Nintendo, even compared to its corporate contemporaries, has a distinctly hostile philosophy around art: if they can’t control something themselves, they tend to try to eliminate it entirely. What Nintendo uses creative rights to protect is not the copyright of their real creative works, it’s their control over everything they perceive to be their “share” of the gaming industry.

Let me start with a quick history, in case you’re not familiar with the foundation Nintendo is standing on.

Nintendo got its start in Japan making playing cards for the mob to commit crimes with. It only pivoted to “video games” after manufacturing playing cards for the Yakuza to use for illegal gambling dens. (I know it sounds ridiculous, but that’s literally what happened.)

Nintendo got its footing overseas by looking to see what video game was making the most money in America, seeing it was Space Invaders, and copying that verbatim with a clone game they called “Radar Scope”:

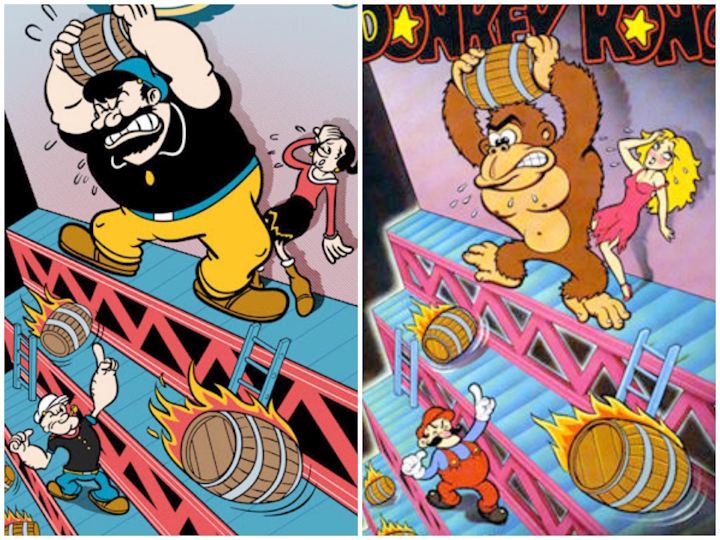

Then, when that was a commercial failure, they wrote “conversion kit” code to turn those cabinets into a Popeye game, failed to get the Popeye rights they needed, and released it anyway. They kept the gameplay and even the character archetypes the same, they just reskinned it with King Kong. They didn’t even name the protagonist after they swapped out the Popeye idea, so he was just called Jumpman.

But then Nintendo was almost itself the victim of an abuse of IP law. “Donkey Kong” derived from King Kong, and even though the character was in the public domain, Universal Studios still sued Nintendo over the use. Ultimately the judge agreed with the Nintendo team and threw out the lawsuit, in an example of a giant corporation trying to steamroll what was at the time a small business with over-aggressive and illegitimate IP enforcement.

This was such an impactful moment for Nintendo that they took the name of their lawyer in the Universal Studios case — Kirby — and used it for the mascot of one of their biggest franchises. It was a significant move that demonstrates Nintendo’s extreme gratefulness — or even idolization — of the man who defended them against abuse of IP law.

You would hope the lesson Nintendo learned here would be from the perspective of the underdog, seeing as they were almost the victim of the kinds of tactics they would later become famous for using themselves. But no, it seems they were impressed by the ruthlessness of the abusers instead, and so copied their playbook.

Apple's Trademark Exploit

Apple's Trademark Exploit

Apple puts its logo on the devices it sells. Not just on the outer casing, but also each internal component. The vast majority of these logos are totally enclosed and invisible to the naked eye. This seems like an incredibly strange practice — especially since Apple doesn’t sell these parts separately — except it turns out to be part of a truly convoluted rules-lawyering exploit only a company like Apple could pull off and get away with.

Remember, trademarks are a consumer protection measure to defend against counterfeits. Apple’s registered logo trademark protects consumers from being tricked into buying fake products, and deputizes Apple to defend its mark against counterfeits.

While some counterfeiting happens domestically the major concern is usually counterfeits imported from foreign trade. This brings us to Customs and Border Patrol, which you might know as the other side of the ICE/CBP border control system. You might be surprised to see them involved with this, since Border Patrol agents are fully-militarized police outfitted to combat armed drug cartels.

But among its other duties, Border Patrol takes a proactive role in enforcing intellectual property protection at ports of trade — backed by the full force of the Department of Homeland Security — by seizing goods it identifies as counterfeit and either destroying them outright or else selling them themselves at auction.1 To get your property back, you have to sue Border Patrol — an infamously untouchable police force — and win.

You've Never Seen Copyright

You've Never Seen Copyright

Hear me out: copyright is good.

When it comes to copyright, it can be very easy to lose the forest for the trees. That’s why I want to start this series with a bit of a reset, and establish a baseline understanding of copyright doctrine as a whole, and the context in which our modern experience of copyright sits.

The current state of copyright law is a quagmire, due not just to laws but also international treaty agreements and rulings from judges who don’t understand the topic and who even actively disagree with each other. That convolution is exactly why I don’t want to get lost in those twists and turns for this, and instead want to start with the base principles we’ve lost along the way.

You don’t need to understand the layers to see the problem. In fact, intellectual property is a system whose convolutions hide the obviousness of the problem. Complexity is good only when complexity is needed to ensure the correctness of the outcome. But here, far from being necessary to keep things working right, the complexity hides that the outcome is wrong.

But that outcome, our current regime that we know as copyright policy, is so wrong — not only objectively bad, but wrong even according to its own definition — that at this point it takes significant work just to get back to the idea that

This is my controversial stance, and the premise of my series: copyright (as properly defined) is a cohesive system, and, when executed properly, is actually good for everyone. And I’m not “one true Scotsman”ing this either; copyright isn’t just an arbitrary legal concept, it’s a system that arises naturally from a set of solid base principles.

The first step in my “understanding the forest for the trees” project is separating the big, nebulous, polluted idea of “copyright” out into the parts people can mostly agree on and the parts that are just evil and bad. Fortunately, the “good” and “bad” groups line up really well with “original intent” compared to “junk that was added later”. Generally speaking, it’s not useful to just make a distinction and act like doing so is the whole job done, unless you just care about smarmy pedantic internet points. But I’m not doing this to be pedantic, I’m making the distinction between the core idea and the junk that’s corrupted it because it turns out to be really important.

What we’re subjected to today in the name of copyright does not come from the real principles of copyright. Compared to the current state of US intellectual property law, the “real copyright” I’m talking about is like grass so utterly smothered by concrete that not only do no strands poke through, everyone involved has forgotten it was ever there.

The situation is so bad that even though I think copyright should be a good thing, I think our current bastardization of it may be worse than nothing at all, to the point where we’d be better off with the problems real copyright is meant to solve than with all the new, worse problems it’s inflicted on us.

But because what we’re enduring now is a corruption of another thing and not its own original evil, we’re not limited to measuring it by the harm it inflicts: we can also measure it by its deviation from what we know it should be.

So what’s the good version? This true, unadulterated form of creative rights?

Is homestuck.giovanh.com official?

Is homestuck.giovanh.com official?

Anonymous asked:

Is your website the official location of the unofficial collection webapp or is it just there now for testing?

I’ve gotten a few variations of this question, so I wanted to get some thoughts down.

The UHC is, itself, unofficial, in that it isn’t acting with the authority of the Homestuck brand, and it’s not a What Pumpkin published work.

https://homestuck.giovanh.com is one further layer more unofficial than that: It’s still not endorsed by Homestuck, but it’s also not necessarily “endorsed” by the main UHC project. It’s a separate spin-off for a couple of reasons, including the fact that it uses some non-free code. But ultimately this separation lets me test experimental features and ideas before they’re released as part of the main collection.

At https://homestuck.giovanh.com/gio, I’ve written

This is an online port of The Unofficial Homestuck Collection, a desktop collection of Homestuck and its related works. TUHC is developed by Bambosh and Gio (and some other great folks), while this port in particular is written, maintained, and hosted as an experiment by Gio.

This is meant as a way to use the offline homestuck collection in a browser, for people on mobile or platforms that don’t have a proper version, or as an “on-ramp” if you’re just getting into Homestuck and aren’t sure if you want to commit yet.

Don’t just use this to read Homestuck! Get the collection; it’s faster, it has real flash, and it costs less to host!

I still think this is the right mentality: if you’re reading through Homestuck or doing fan work, you probably still want the main desktop release. It’s also much more moddable; the browser version has some modding functionality, but it’s stripped down and isn’t ever going to be up to the standard of the main collection.

I think what this question might mean to be asking is: “is https://homestuck.giovanh.com temporary?” The answer to that is no: I don’t have any plans to stop hosting it, and if we ever move to a different URL, I’ll set something up to redirect https://homestuck.giovanh.com there, including the page references, so links won’t break. You should be able to safely share links to the web collection, including homestuck pages (https://homestuck.giovanh.com/mspa/001901) and collection metapages (https://homestuck.giovanh.com/search/fiddlesticks) (as possible).

I don’t currently have any plans to move the domain name, though. I can imagine doing that at some point in the future, if governance ever changes (i.e. it’s not strictly personal, and so shouldn’t be on my personal) but I already own giovanh.com, and I think Homestuck fits nicely there.

The Angel is You

The Angel is You

”…okay, fine, you can have one more, but only because of the name”

a Deltarune theory

Answering the questions raised by Ralsei’s prophesy:

First, here’s a list of all the references to “Angels” or “Heaven” in the text of Undertale and Deltarune, which I’ll go through one by one:

First, the “angel” (lowercase) from Undertale, which I’ll ultimately want to write off as a distraction.

In Waterfall, you can ask Gerson about the Delta “with-a-space” Rune, the royal emblem, and he’ll exposit:

My Pal Sorter

My Pal Sorter

I’ve decided to do a short write-up on a tool I just call “Sorter”. Sorter is something I built for myself to help me organize my own files, and it looks like this:

It’s designed to do exactly one thing: move files into subfolders, one file at a time. You look at a file, you decide where it goes, and you move it accordingly. It’s the same behavior you can do with Explorer, but at speed.

You can download it if you want (although it might not be easy to build; check the releases for binaries) but for now I just wanted to talk through some of the features, why I built it the way I did, and the specific features I needed that I couldn’t find in other software.